Last year my niece and her husband were traveling through Iowa. They stopped at a rest area near Wilton. Afterward she sent me the following pictures.

The Iowa government website, traveliowa.com, says this about the display:

When you’re driving on I-80 by Wilton, you won’t want to miss the interstate rest area that features interpretive panels that explain Cedar County’s involvement in the Underground Railroad as well as the story of the “Underground Railroad Quilt Code.” Secret messages were hidden in quilts through geometric patterns and the sequencing of stitches and knots to “map” the path slaves should follow to freedom. These safe routes were displayed in the everyday custom of hanging quilts out to dry.

I’ve never stopped at this rest area before. If I had, I would have been quite dismayed to see the displays. The fact is, there is no proof and no reason to believe quilts were used to convey secret messages. Below the bar I’ve reposted a story I first published three years ago, which tells the whole story.

Did quilts help guide escaped slaves to safety? Did different quilt blocks have specific meanings to slaves, perhaps based on their African past? Was the pattern of stitches and knots informative about routes to take, perhaps creating a topographical map?

The most famous telling of a quilt code says that indeed, quilts were a vital part of the Underground Railroad, and their history with it was unwritten until very recently.

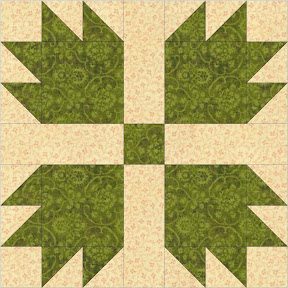

One of the blocks in the quilt code is the Bear’s Paw, shown here.

This pattern consists of several squares, rectangles, and right triangles. When different scraps of fabric are used, the pattern takes on the complexity of a map that is remarkably similar in design to the African Hausa embroidered map of a village …Just as the Hausa design defines the perimeter of the village and identifies major landmarks, the Bear’s Paw pattern could be used to identify landmarks on the border of the plantation …

Because the bears lived in the mountains and knew their way around, their tracks served as road maps enabling the fugitives to navigate their way through the mountains. … The bears’ trails formed a map.

From Hidden in Plain View, by Jacqueline L. Tobin and Raymond G. Dobard, Ph.D.

Slaves escaped in all directions. We are used to thinking of them traveling north to Canada. But in fact they also went south to Mexico and Spanish Florida, disappeared into cities and remote areas, and took shelter with Native American communities. Best estimates are that between 40,000 and 100,000 slaves successfully escaped northward. Most escaped on their own, getting help only after reaching the North.

The Underground Railroad is attributed with helping to move slaves to freedom during the late-1700s to mid-1800s. (Freedom activism long preceded the phrase “Underground Railroad,” which wasn’t used until the 1830s.) Not a physical railroad, of course, it was an “underground” movement of abolitionists and allies, with a web of routes and safe houses. Those slaves who escaped endured incredible trials of strength and courage.

There are documented truths about the Underground Railroad, from those who made it function and those who escaped. But it also has been romanticized and mythologized. It is not always easy to separate fact from fiction.

Hidden in Plain View?

Prior to 1999, there were few known sources claiming the existence of a quilt code. According to wikipedia,

The first known assertion of the use of quilts … was a single statement in the narration of the 1987 video Hearts and Hands, which stated “They say quilts were hung on the clotheslines to signal a house was safe for runaway slaves.” This assertion does not appear in the companion book and is not supported by any documentation in the filmmaker’s research file.[1] The first print appearance of such a claim was Stitched from the Soul, a 1990 book by folklorist Gladys-Marie Fry, which states — without providing any source — “Quilts were used to send messages. On the Underground Railroad, those with the color black were hung on the line to indicate a place of refuge (safe house)…Triangles in quilt design signified prayer messages or prayer badge, a way of offering prayer. Colors were very important to slave quilt makers. The color black indicated that someone might die. A blue color was believed to protect the maker.”[1] …

The idea, clearly presented as fiction in Sweet Clara and the Freedom Quilt, that slave quilts served as coded maps for escapees, entered the realm of claimed fact in the 1999 book Hidden in Plain View, written by Raymond Dobard, Jr., an art historian, and Jacqueline Tobin, a college instructor in Colorado.[3]

In 1999, the stories of a woman named Ozella McDaniel Williams were published in the book Hidden in Plain View, by Jacqueline L. Tobin and Raymond G. Dobard, Ph.D. The book also includes a mesh of related research about African symbolism, escape routes, and information about the times.

Author Tobin met Williams in 1994. Williams was a South Carolina quilt vendor at a flea market mall. In 1997 during their second of three meetings, “Ozella,” as the book refers to her, told Tobin stories she claimed were passed down through her family. This oral history, if confirmed, would change our understanding of methods of communicating about the Underground Railroad and routes to freedom.

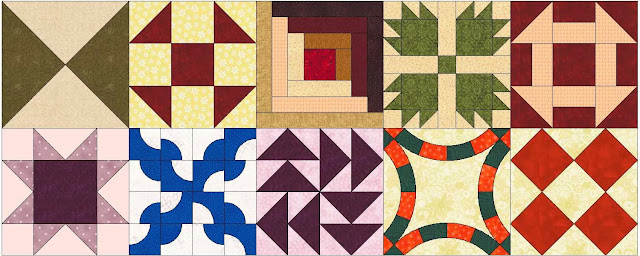

According to Williams, there were eleven quilt blocks in the code. The blocks were sewn into quilts, which would be displayed one at a time on fences or clothes lines. Because it was normal to air quilts regularly, showing the quilts this way wouldn’t arouse suspicion by owners or overseers.

The blocks shown below are woven into Williams’ version discussed in the book. Some versions include other blocks, as well.

A short version of the code says

The Monkey Wrench turns the Wagon Wheel toward Canada on a Bear’s Paw trail to the Crossroads. Once they got to the Crossroads, they dug a Log Cabin on the ground. Shoofly told them to dress up in cotton and satin Bow Ties and go to the cathedral church, get married and exchange Double Wedding Rings. Flying Geese stay on the Drunkard’s Path and follow the Stars.

The book presents this very short interpretation, but it includes linkages and suppositions and speculations about the meanings of all the blocks, as well. For example, the Bear’s Paw block shown above is interpreted as both a map of the plantation itself, as well as advice to follow actual bears’ trails over the mountain.

About another, the Monkey Wrench block, the authors state, “Ozella told us that a quilt made of Monkey Wrench patterned blocks was the first of the ten quilts displayed … a signal for the slaves to begin their escape preparations” and gather physical and mental tools.

Along with this understanding of the block, the authors include discussion of the role of the blacksmith on the plantation, with tools including the monkey wrench. The blacksmith’s metal-working ability may have hidden the smith’s function of conveying information to other slaves under the ring of the hammer. A photo of an African textile is shown, to further convey the importance of tools in the previous environment.

More than 120 years after the Emancipation Proclamation, claims of a quilt code arose. Had the evidence been missed all those years? Was the truth really hidden in plain view?

What is the Truth?

To anyone used to reading academic research, even in laymen’s terms, Hidden in Plain View clearly falls short. In fact, the book reads as one long, breathless speculation on the possibility that quilts were used to help guide slaves to freedom. The linkages to African symbolism in art and song do not confirm or deny the potential. This alone does not negate the premise. Finding the truth is somewhat more difficult.

Historians, including those with expertise in quilts and other textiles, eagerly reviewed the possibilities to answer the question: Were quilts used to help guide slaves to freedom?

Strong evidence in support could consist of testimony of escaped slaves, or from former slaves after emancipation; testimony from freedom activists; public records or contemporary writings; or remaining textiles with long provenance and supporting documentation, among other things. Weaker evidence in support might include other contemporary information such as textile availability and use, for example; or direct linkages between African symbolism and the quilt code.

If none of this evidence exists, there is no support for the claim that quilts were used as part of an Underground Railroad communication system, helping slaves to escape.

Did slaves make quilts, and are there existing quilts that provide provenance on this?

We do know that slaves made quilts. Surviving examples made prior to Emancipation are mostly those made for owners, rather than for the slaves themselves. Despite the abundance of cotton in the South, fabric was scarce even before the Civil War began. The South had very few mills, and they were small, mostly making rough cloth. Most finer fabric came from the North or from Europe.

For their own use, many quilts made by slaves would have been “utility” quilts. (This may have depended largely on regional differences, as well.) These had rougher fabric, simpler construction, and ties or long stitches of thick threads, rather than fine quilt stitching. Woven blankets were more prevalent than quilts. Slaves were typically issued one blanket each two years. Washed with lye, both types of bed covers disintegrated over time. Clothing provisions also were meager, and using remnants or scraps from “old” clothes to make quilts was unlikely.

There are no existing quilts known that have documentation of being used to signal or communicate escape information.

Did slaves make quilts using the blocks in the purported quilt code?

Some of the blocks are documented from pre-Civil War. Others are not. One problem with documentation is that blocks were assigned different names in different regions, or at different times. Also there may be multiple block designs that have the same name. Assuming that one design always went by the same name is problematic.

For example, the Bear’s Paw design shown above is now considered a traditional block. Most quilters today, if they know block names, would call it a Bear’s Paw. Ozella Williams called it a Bear’s Paw. But Barbara Brackman, a premier quilt historian, documents three different blocks by the same name in her Encyclopedia of Pieced Quilt Patterns. Which one was used, if any?

Other blocks show no history of use before the Civil War. Double Wedding Rings is a design that originated in the late 1920s. Log Cabin blocks were popularized during the Civil War.

From Leigh Fellner’s extensive review of the quilt code: (this link is no longer active)

In fact, the Log Cabin pattern seems to be limited to the North as a popular expression of Union sentiment; I have not been able to find any documented examples dating from before the Civil War. Quilt historian Barbara Brackman notes in Quilts from the Civil War that the earliest date-inscribed quilt of this pattern is dated 1869: “Quilt historian Virginia Gunn has found three written references to Log Cabin quilts as fundraisers for the union cause in 1863, the likely year for the beginning of the style. At that point the underground Railroad no longer functioned as it had before the War….So we must not imagine Log Cabin quilts as signals in the decade before the War. Rather, like Emancipation, the pattern grew out of the War. It is more historically accurate to view their symbolic function as an indicator of allegiance to President Lincoln and the Union cause…One indication that a Union connection [with the pattern] continued is the relative lack of late nineteenth-century Log Cabin quilts made in the former Confederate states.”

How would the quilts have been used to communicate?

According to Williams in Hidden in Plain View, quilts would have been used to communicate before escaping. With ten different quilts showing the different blocks, each would signal a specific piece of information. Wouldn’t it be easier to communicate most of this in words rather than in a semaphore-like system?

Also, the authors (not Williams) imply that the quilts may have been used en route, for instance to signal safe houses. Because most travel was in the safety of darkness, how would a runaway slave find the quilt, and see it well enough to interpret it? They discuss different colors as having particular meanings, but this becomes especially problematic in darkness.

Are there any documented first-hand reports of quilts used to communicate in code?

Historians’ examination of the written record does not uncover this communication. Pamphlets and books with first-hand accounts, including histories taken by the WPA in the 1930s, do not provide evidence of this communication.

I reviewed text of the book Underground Rail Road by WIlliam Still. Still helped hundreds of slaves escape, and interviewed each. His book does not include any mention of quilts used to escape. Two other sources include Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936-1938, and North American Slave Narratives, a collection of the University of North Carolina, which includes “all the existing autobiographical narratives of fugitive and former slaves published as broadsides, pamphlets, or books in English up to 1920.” I did not examine these records myself, but am reporting the consensus of several historians.

Other than the oral history reported by Ozella Williams and a handful of others who came after her, there is no support for the use of quilts this way.

Is there other evidence presented in the book that provides firm support for the premise?

No. The book includes lengthy discussion of secret societies and the role of the griot (historian/storyteller) in African societies. It continues with supposition on the Freemasons and the ability of free blacks to travel to the South without repercussions. African symbolism and spiritual songs are linked to the quilt code as well. But none of these provide evidence of a quilt code, merely weak support of the possibility.

The authors also depend substantially on present-day children’s literature for support, books like Sweet Clara and the Freedom Quilt by Deborah Hopkinson. It’s actually a lovely book — I’ve bought it myself — but it is fiction, not academic research.

Conclusion: reputable historians of both the Underground Railroad and of quilts agree: there is insufficient evidence to support the premise that a quilt code was used to communicate this way.

Does it Matter?

Does it matter if this story is told and believed, even if it is not true? Is it harmful to let it persist?

I believe it is harmful. It provides a romanticized version of an ugly past. It allows us to imagine that slave women had leisure and resources to create beautiful bedding for their own use. Though some surely did, that was not typical. If the quilts were not their own, it’s implied they somehow had access and power to decide which of the owner’s quilts to air (and signal) and at what time.

It suggests that “African” symbolism was consistent across all cultures, and all slaves would interpret the textile symbols in consistent ways. This minimizes the richness and complexity of the various cultures from which they came.

The book Hidden in Plain View is factually incorrect in many places, and depends on speculation for most of the rest. Readers who believe this source of information will perpetuate the stories. Ozella Williams was a quilt vendor. She may have told the stories in good faith, or she may have told the stories to sell quilts. The potential conflict of interest should not be ignored.

School curricula on slavery and the Underground Railroad that include this “history” are wrong. Schools began including the story in the early part of the new century. As I researched for the post, I found many suggested lesson plans, still in existence. Typically, the plans suggest having students design quilts using the code blocks. The children are learning lies.

And now there are at least a couple of popular authors of adult historical fiction, who include this premise in their plot lines. When I presented on this topic recently to a group of twenty, most of them came to the presentation assuming the myth was fact. Several attributed it to the novels they had read.

Truth is strength. We don’t need to pretty it up with cozy quilts and homey images. We owe it to those who suffered slavery, to ourselves and our children, and to the future, to know and tell the truth.

stored without loosing yield or quality prior to ginning. Specially designed trucks pick up modules of seed cotton from the field and move them to the gin. Modern gins place modules in front of machines called module feeders. Some module feeders have stationary heads, in which case, giant conveyors move the modules into the module feeder. Other module feeders are self-propelled and move down a track that along side the modules. The module feeders literally break the modules apart and “feed” the seed cotton into the gin. Other gins use powerful pipes to suck the cotton into the gin

stored without loosing yield or quality prior to ginning. Specially designed trucks pick up modules of seed cotton from the field and move them to the gin. Modern gins place modules in front of machines called module feeders. Some module feeders have stationary heads, in which case, giant conveyors move the modules into the module feeder. Other module feeders are self-propelled and move down a track that along side the modules. The module feeders literally break the modules apart and “feed” the seed cotton into the gin. Other gins use powerful pipes to suck the cotton into the gin  building. Once in the cotton gin, the seed cotton moves through dryers and through cleaning machines that remove the gin waste such as burs, dirt, stems and leaf material from the cotton. Then it goes to the gin stand where circular saws with small, sharp teeth pluck the fiber from the seed.

building. Once in the cotton gin, the seed cotton moves through dryers and through cleaning machines that remove the gin waste such as burs, dirt, stems and leaf material from the cotton. Then it goes to the gin stand where circular saws with small, sharp teeth pluck the fiber from the seed. made into dense bales weighting about 500 pounds. To determine the value of cotton, samples are taken from each bale and classed according to fiber length (staple), strength, micronaire, color and cleanness. Producers usually sell their cotton to a local buyer or merchant who, in turn, sells it to a textile mill either in the United States or a foreign country.

made into dense bales weighting about 500 pounds. To determine the value of cotton, samples are taken from each bale and classed according to fiber length (staple), strength, micronaire, color and cleanness. Producers usually sell their cotton to a local buyer or merchant who, in turn, sells it to a textile mill either in the United States or a foreign country. overseas. U.S. textile manufacturers use an annual average of 7.6 million bales of cotton. A bale is about 500 pounds of cotton. More than half of this quantity (57%) goes into apparel, 36% into home furnishings and 7% into industrial products. If all the cotton produced annually in the U.S. were used in making a single product, such as blue jeans or men’s dress shirts, it would make more than 3 billion pairs of jeans and more than 13 billion men’s dress shirts.

overseas. U.S. textile manufacturers use an annual average of 7.6 million bales of cotton. A bale is about 500 pounds of cotton. More than half of this quantity (57%) goes into apparel, 36% into home furnishings and 7% into industrial products. If all the cotton produced annually in the U.S. were used in making a single product, such as blue jeans or men’s dress shirts, it would make more than 3 billion pairs of jeans and more than 13 billion men’s dress shirts.